Before you begin, please read through the instructions to see where you are headed with each step. This will also tell you whether the effort involved is worthwhile for your farm. Earlier chapters in this manual provide many suggestions as to how to think about the problem of developing general crop rotation plans and specific crop sequences. Tables in the appendices provide a wealth of factual information to help you avoid problems and take advantage of opportunities related to particular cropping sequences. Becoming familiar and consulting with that information will help you work through the steps that follow. The procedure may prompt you to rethink your farming operation and crop mix, as you order the sequence of crops on particular fields.

If you are using the Excel worksheets mentioned above, skip this step.

Otherwise, make several copies of table 5.1 (Crop Characteristics Worktable, page 61). You will need enough copies so that each planting of every crop during a typical year can have one line. You may find a few extra copies useful, as well.

Make several copies of table 5.2 (Field Conditions Worktable, pages 62–63). Note that the table consists of two separate sheets (parts A and B), and you will need multiple copies of each sheet. How many copies you make to start with depends on how accessible the nearest copier is. The exact number of copies you will need cannot be determined at the outset, but you can determine

the approximate number of copies as follows: Divide the cropped area of the farm by the acreage of your smallest acreage crop. You probably will not need more than that number of copies. You probably will need at least a fourth of that number.

Make copies of table 5.3 (Field Futures Worktable, pages 64–67). Make as many copies of this table as you made of table 5.2. Note that the Field Futures Worktable consists of four sheets (parts A–D), and you will need multiple copies of at least the first two sheets. Whether you need to copy the third and fourth sheets depends on how far forward you want to plan.

Cut your copies of the Field Conditions Worktable, part B, along the vertical line between “Manage unit” and “Current winter.” Now tape each part B sheet to each part A sheet to make one extra-wide sheet. “Current winter” should now be next to “Crop last summer” on Part A.

Discard the scrap with “Zone” and “Manage unit.” Place a long piece of tape on the back where the two sheets meet, as eventually you will need to cut the sheets lengthwise to sort the lines.

Repeat the cutting and taping for the Field Futures Worktable. The column for “Two winters from now” on part B should end up adjacent to “Two summers from now” on part A. Again, discard the scrap. Depending on how far forward you are planning, add parts C and D to the strip.

2. Set rotation goals

Identify what you would like your crop rotation to accomplish. Sidebar 2.8 (page 14) provides a list of potential rotation goals developed by experienced organic farmers. The fictional example of Small Valley Farm will be used to illustrate various steps in the planning process (sidebar 5.2). Their rotation goals are as follows:

3. Prioritize your goals

Order your goals. This is particularly useful if you have a long list of goals, since you may find it impossible to meet all of the goals completely every year. Some goals may be so easily met that, although they are critical, they need little attention in the rotation planning process. For Small Valley Farm, providing N for the crops is economically important, but since one third of the land is in nitrogen building grass-alfalfa hay each year and a clover cover crop can be interseeded into either oat or spelt, providing sufficient N is easy to accomplish. Consequently, the farm’s goals are prioritized as follows:

Sidebar 5.3

Codes for Recording Planting and Harvest Times

Generally, attempting to target particular planting and harvest dates too carefully will

prove futile due to the unpredictability of the weather. The following codes may be useful for tracking when you plant and harvest. If you have a long growing season, you may want to divide spring and fall into three categories instead of two. You can also create your own codes, but be sure to record them somewhere!

| Time | Code |

| Early spring | espr |

| Late spring | lspr |

| Early summer | esum |

| Midsummer | msum |

| Late summer | lsum |

| Early fall | efall |

| Late fall | lfall |

Sidebar 5.4

Minimum Return Time

A minimum return time of four to five years will prevent most soil borne diseases (appendix 3, pages 124–137), provided you practice good sanitation measures (see “Managing Plant Diseases with Crop Rotation,” page 32). A shorter return time can be used for grass family crops, particularly if the rotation includes some alternation of corn, small grains, and forage grasses. Although these different grass family crops share a few diseases (see appendix 2, pages 104–123), avoiding rapid return to a particular grass species is usually sufficient to avoid disease problems.

4. Write down your desired crop mix for the coming year

Make a list of the crops you grow and how many acres, beds, or square feet you want to grow of each crop to meet your market requirements. Use your copy of the Crop Characteristics Worktable to organize the list by families. (Look up the family of your crops in appendix 1, pages 101–103, if necessary.)

Next, for each crop family, group crops that you grow using similar practices and planting and harvest times. Members of these crop groups are functionally equivalent with respect to many aspects of crop rotation.

Fill in the name of each crop you plant down the lefthand column. If you plan to make multiple plantings of a crop, enter each planting on a separate line with a unique name (for example, lettuce 1, lettuce 2, etc.). Separating plantings is useful because each has different planting and harvest times and therefore has different cash and cover crops that can precede or follow it. For crops that remain in the ground for several years, you may find listing each crop year useful (for example, strawberry yr 1, strawberry yr 2, etc.). Table 5.4 shows the crop mix for Small Valley Farm.

5. Add crop characteristics to the Crop Characteristics Worktable

Now look at your Crop Characteristics Worktable, and going across the page add column titles in spaces to the right of “Net $/acre” that you think will be useful in deciding either the sequence in which you order crops or where the crops will be placed on the farm. Crop characteristics that expert farmers take into account when planning their rotations are listed in sidebar 2.9 (page 15). Including columns for target planting and harvest times will be useful if you plant some crops multiple times during the season or if you grow many different crops. Next, fill in the appropriate information for each crop in the various columns. For now, ignore the column headed MUs/year—you will use that later. For crops that are harvested repeatedly, the final harvest is the critical time relative to crop rotation, since that is when the field becomes available for planting the next cash or cover crop. Sidebar 5.3 provides codes for planting and harvest times that fit easily on the worksheet. Enter the net income per acre (or other unit of land area). This information will be used to help prioritize where crops go. Approximate numbers are good enough—you just need to be able to tell the ranking of values for the various crops. Copy from appendix 1 (pages 101–103) any information you think is useful for sequencing crops on your farm.

| Crop | Acres/year |

| Tofu soybean | 120 |

| Corn | 120 |

| Oat/clover/spelt | 120 |

| Spelt/hay (1st year) | 120 |

| Hay (2nd year) | 120 |

| Hay (3rd year)/oat cc | 120 |

6. Check for lack of diversity in your crop mix

Scan your worktable and determine which plant family will have the greatest area. For this computation, ignore the grass family (see sidebar 5.4). Add up the area for the most widely planted, non-grass family. Now divide the total cropped area of the farm by the area of that family. This number represents the average rotation return time for the most common non-grass crop family you grow. For example, if the average rotation return time is 4, the most prevalent non-grass plant family will occur on a given location once in every four years, provided you are careful to ensure a maximum lag between planting members of that family throughout the farm. Of course, many factors, including field-to-field variation in soil conditions, production of perennial crops, and changes in cropping plans due to weather will lead to shorter return times at some locations. If the average rotation return time for the most prevalent family is less than 4, check appendix 3 (pages 124–137), and consider renting additional land or changing your crop mix so that a smaller percentage of the farm is planted with that family. Sidebar 5.5 shows an example of return time calculation.

Suppose a farm has the crop mix shown below:

| Crop | Family | Number of Beds |

| Lettuce | Lettuce | 6 |

| Onion | Lily | 6 |

| Leek | Lily | 3 |

| Garlic | Lil | 3 |

| Tomato | Nightshade | 6 |

| Potato | Nightshade | 6 |

| Pepper | Nightshade | 4 |

| Green bean | Legume | 4 |

| Pea | Legume | 4 |

| Carrot | Carrot | 2 |

| Summer squash | Cucurbit | 4 |

| Total | 48 | |

The most prevalent crop family is the nightshades, with 16 of the 48 beds. Average return time for nightshades is 48/16 = 3 years. That is, a given piece of ground will have a nightshade crop every third year, even if the sequencing is ideal. This may be too frequent for long-term prevention of soil borne diseases of nightshade crops (see appendix 3, page 124–137). The second-most prevalent group are the alliums in the lily family, with an average return time of 48/12 = 4 years. Consequently, shifting from nightshades to an increase in alliums will not help diversify the crop mix appreciably. With such rapid return times for two major families, the farmer should consider either expanding his land base or developing markets for crops in other families.

7. Identify crop sequences that you use repeatedly

Look at your planting records and list all the 2- and 3-year crop sequences that you have found work well on your farm. These form the backbone around which you will build your rotation plan. You will probably find that these reliable sequences meet certain rotation goals or make your operation run smoothly. Note what each sequence is doing to facilitate your operation. This will

allow you to explore alternative sequences that provide the same benefits. For Small Valley Farm, sequences and notes might look like this:

The “Real Fields on Real Farms” color plates in chapter 4 (pages 49–54) provides many examples of sequences that farmers use successfully. Appendix 2 (pages 104–123) shows problems and opportunities associated with various crop sequences.

8. Identify areas of your land that offer special opportunities or pose problems.

Identify fields and parts of fields that grow certain of your crops particularly well or pose production problems for particular crops. Note these areas on a map of your farm. Table 5.5 (page 74–75) provides a list of field characteristics that experienced growers take into account when planning crop rotations.

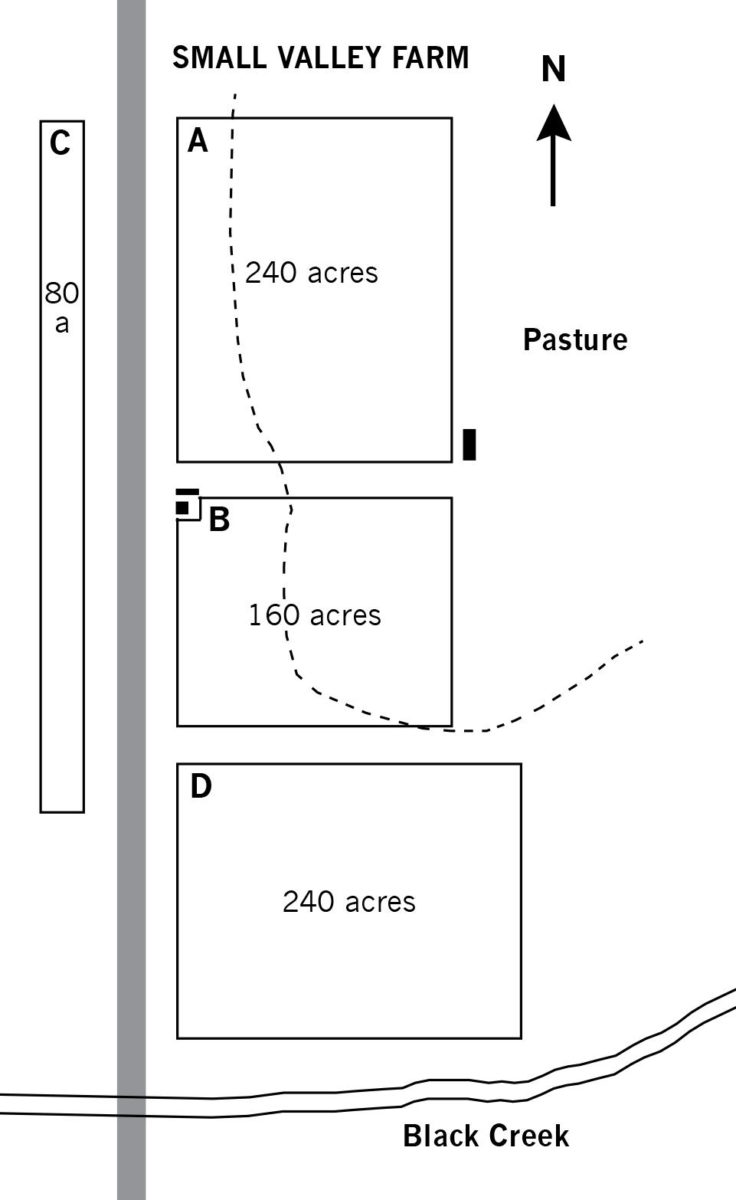

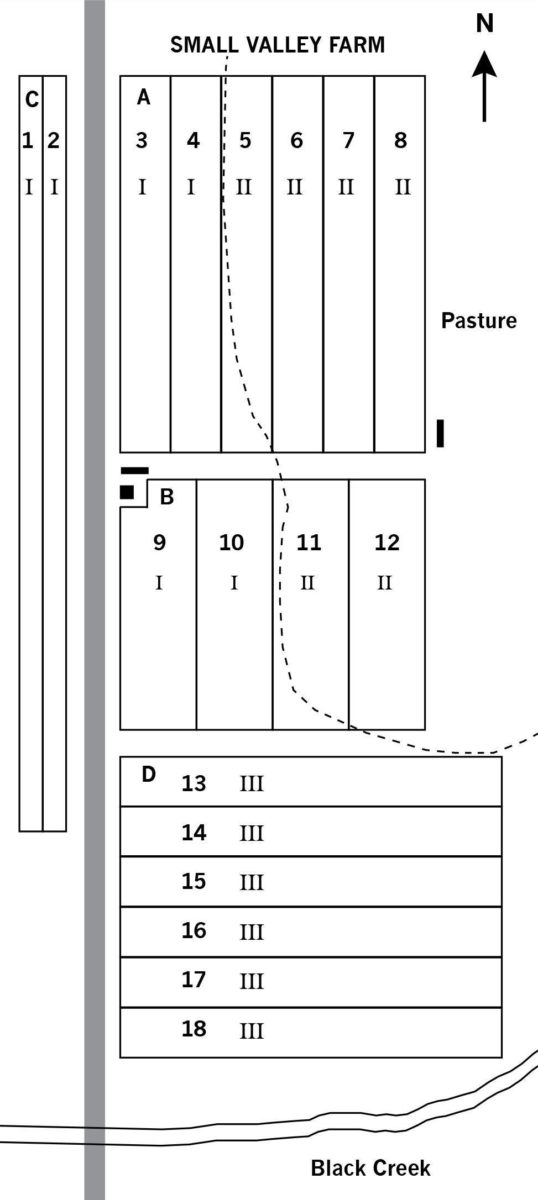

For Small Valley Farm, the main problem area is the east side of fields A and B, which slopes too steeply for safe production of row crops (figure 5.2). Field D is flat, fertile bottomland that can support intensive row crop production.

Choose a few of these field characteristics that you think are most critical for planning your rotations, and based on them, categorize the fields into a few basic types. Realize that you will probably need a separate rotation plan for each type of field. Consequently, choose the most important field characteristics on which to focus. Meshing many separate rotations to get your desired crop mix each year will become hopelessly complex, particularly if you are producing many crops. Therefore, if you have many critically different types of fields or if you grow

many crops and all land is cash-cropped each year, do not bother developing a general rotation plan. Instead, skip to step 11. On the other hand, if you grow fewer than eight types of cash crops (the crop groups discussed in step 4) and have only one to three types of fields, you will probably benefit from development of a general rotation plan. Similarly, if you rest at least a third of your land each year without planting cash crops on it, consider developing a general rotation plan. See figure 5.1 (page 60).

9. Divide the farm into field types.

Based on your map and notes from the previous step, block the farm into field types. All land with a particular field type should be suitable for growing the same set of crops. Note that if all areas of the farm are reasonably suitable for all crops, you are lucky to have only a single field type to deal with. Areas of a particular field type do not have to be adjacent, and field types do not have to cover equal areas of the farm (in the Small Valley Farm example (table 5.6, page 77), the areas in the three field types were made equal to simplify the illustration).

Small Valley Farm has the following field types:

10. Propose reasonable crop rotations for each field type.

Using your short, 2- or 3-year sequences and other short sequences you think might work, develop a preliminary rotation for each of the field types on your farm. Make the crop rotations in each of the field types have the same number of years (cycle length) in the rotation or an exact multiple of the shortest rotation length. Otherwise, meshing the rotations to achieve your desired crop mix each year will be difficult.

Although the Small Valley rotation plan discussed below focuses on particular crops, many farmers prefer to focus on crop types. These crop types could be botanical families or relate to the season when the crop is in the ground. For example, the Nordells’ rotation plan, presented in chapter 4’s “Real Fields” chart (pages 49–54), alternates spring-planted crops with a year of fallow and cover crops and then summer-planted crops. Basing the rotation plan on planting time can simplify field operations by synchronizing them over substantial blocks of land. However, if your rotation plan is based on crops grouped by planting time, you may need to make additional provisions to ensure that botanically similar crops are not grown too closely in the sequence. This could be accomplished, for example, by repeating the basic planting time sequence with different families in each repetition.

The Small Valley farmers decided on the following rotations:

Essentially, the Small Valley farmers moved the row crops and spring grain from field type II to field type III, leaving only erosion-resistant sod and winter grain crops on the erosion-prone land of field type II. Over the course of the six-year cycle, the mix of cash crops has not changed at all. Placing these crop sequences on particular plots of land to achieve the desired crop mix in each year, however, still requires some additional planning.

Experienced growers have identified the factors listed here as factors they note when planning crop sequences. The table is laid out to show column title codes and abbreviations that are useful when filling out the Field Conditions Worktable (table 5.2, pages 62–63) in steps 17 through 19. Management units (MUs) are pieces of land of uniform size, each of which is farmed as a block. The usefulness of dividing the farm into uniformly sized management units is discussed in step 11.

| Column title | Explanation |

| Field name | Your name for the field—e.g., SW, upper creek. |

| Field type | Parts of the farm that share a common rotation plan—I, II, III, IV, etc. See optional steps 9–10. |

| Mgmt. unit | Number of this MU. Each unit should have a unique number. Number adjacent units sequentially |

| Field history | |

| Crop 3 summers ago | Names of crops (and cover crops) three summers ago. |

| Crop 2 winters ago | Name of cover crop or crop two winters ago. |

| Crop 2 summers ago | Names of crops (and cover crops) two summers ago. |

| Crop last winter | Name of last winter’s cover crop or crop. |

| Crop last summer | Names of last summer’s crops (and cover crops). |

| Current winter—crop | Name of the current cover crop or crop. |

| Current winter—plant | Planting time of the current cover crop or crop. |

| Current winter—harv. | Expected harvest or incorporation time of the current cash crop or cover crop. |

| Field Characteristics that can be entered in the blank columns of the Field Conditions Worktable | |

| Soil series | Name of the soil series from your county soil survey. |

| Texture | SaL (sandy loam), SiL (silt loam), CL (clay loam), etc. Obtain this from your county soil survey but temper it with your judgment. |

| Drainage | E (excessive—droughty), W (well), MW (moderately well), SP (somewhat poor), P (poor). |

| Slope | Percent slope of the MU. Enter range if it varies. |

| Aspect | Direction the land slopes: N, NE, E, etc. C for complex slopes, F for flat. |

| Irrig? | Is irrigation available? Y (yes), N (no). |

| Shaded? | Is the MU shaded by trees or steep hills? Y (yes), N (no). |

| Air drain. | Air drainage. G (good), I (intermediate), P (poor). Air drainage affects tendency toward late spring and early fall frosts. |

| Air circ. | Air circ. E (exposed), I (intermediate), S (sheltered). Exposed fields may be susceptible to wind damage; sheltered fields may be more susceptible to spread of disease. |

| Access | Access G (good—e.g., near farmstead), I (intermediate), P (poor—e.g., the other side of the woodlot). |

| Visibility | Visibility VV (very visible) , V (visible), H (hidden). You may prefer to put crops that attract customers near the road, and experiments that may fail where they cannot be seen. |

| Neighbors | Neighbors Note issues with neighbors—e.g., may not want to spray next to homes; pollen drift from conventional growers. |

| Moist. hold. cap. | Moisture holding capacity. G (good), I (intermediate), P (poor). |

| Org. matter | Enter range of recent percent organic matter values. |

| Org. mat. qual. | Your judgment of the quality of the organic matter. Is it well decomposed to humus, or is a lot of coarse fiber and wood present? G (good), I (intermediate), P (poor). |

| Tilth | Your judgment of the tilth of the soil. G (good—tilled soil is loose, with little tendency to crust), I (intermediate), P (poor—tilled soil is cloddy, compacted, tends to crust). |

| Aggregation | G (good—soil has good crumb structure), I (intermediate), P (poor—soil is massive and blocky or loose sand with few crumbs). |

| Nut. release | Ability of soil to release nutrients to the crop. G (good), I (intermediate), P (poor). |

| Nut. imbal? | Note any nutrient imbalances—e.g., poor Ca:Mg or Ca:K ratios. |

| Erosion | Tendency toward erosion if soil is left uncovered. H (high), I (intermediate), L (low). |

| Deer pres. | Deer or other animal pressure. H (high), I (intermediate), L (low). |

| Dis. crops | List crops that in this MU have had a recent history of soilborne diseases. |

| Diseases | Names of the diseases of the crops just listed. |

| Ann. weeds | Annual weed pressure. H (high—many annual weeds if not controlled), I (intermediate), L (low—little history of annual weed problems). |

| Worst ann. spp. | List the worst annual weed species. |

| Peren. weeds | Perennial weed pressure. H (high—perennial weeds have posed problems recently), I (intermediate), L (low—little history of perennial weed problems). |

| Worst peren. spp. | Worst peren. spp. List the worst perennial weed species. |

11. Draw a crop rotation planning map.

This map may need to be more detailed than the map you use for organic certification. Begin by noting

the dimensions of each field on the map. In this step you will subdivide fields into small management units (MUs) of approximately equal size across the whole farm. Only one crop will be grown on any particular MU at a time, and usually several MUs will be required to grow the full acreage of a crop in any given season. Crops will move from one block of MUs to another between years. Dividing the farm into management units allows accurate record keeping and helps you to stay organized when moving

crops between fields that vary in size, shape, and other important characteristics.

Figure 5.3 (page 76) shows how Small Valley Farm laid out its 40-acre MUs across the farm. Since the farm has a total of 720 tillable acres, it has a total of 18 MUs. Appendix 6 (pages 148–149) provides easy instructions for making rotation planning maps using Microsoft Excel. Consider the following points when determining the size and arrangement of your management units:

Now divide the fields into management units on your map. Note that small variations in the size of MUs due to irregularities in field shape are unavoidable but probably will not matter much since most crops will be grown on several to many MUs.

12. Record your crop mix in terms of management units.

On your Crop Characteristics Worktable, record how many management units you want to grow of each crop. You already have the amount of each crop recorded in acres, square feet, or some other unit, but converting these to MUs will simplify thinking about how you sequence the crops on particular MUs. If you made an error in the previous step, the conversion of area to MUs may result

in some crops being grown on fractions of an MU. In this case, adjust your crop mix slightly, so that all crops will be grown on a round number of MUs.

13. Number each management unit.

Put the number of each MU in the upper left corner of each management unit on the map. Make the numbers sufficiently large and legible that they will photocopy well. Blocks of land that you commonly manage together should be numbered sequentially.

14. Make several copies of the maps.

You will need at least eight copies of the maps, and a few more may be useful later. Be sure to save the original map in a safe place for making future copies. And be sure to label each map as you complete steps 15–16.

15. Record especially valuable MUs on one copy of the maps.

You noted the most important field characteristics in a general way in step 8. Now it is time to characterize each MU in detail. Note MUs that have especially useful properties on one copy of the map. Favorable properties may include proximity to the farmstead, access to irrigation if irrigation is limited, slope or drainage characteristics that allow early planting, and many others (see table 5.5, page 74). Note only exceptional properties on the map. Writing something for each MU would be time consuming and is not necessary. Use the abbreviations in table 5.5 if you are cramped for space.

16. Record problem MUs on another copy of the map.

Label another copy of the map, and note on that copy management units with problems that restrict the types of crops you can grow. Such problems include poor soil drainage, severe animal pressure, shadiness, frost pockets, and slope characteristics that lead to slow warming in the spring. See table 5.5 (pages 74–75) for a list of characteristics assembled by experienced growers.

17. Number MUs on your Field Conditions Worktable.

Put the field name and number of each MU on a line in the Field Conditions Worktable (your copy of table 5.2, pages 62–63). Number the MUs sequentially. If you did steps 9 and 10 above (general rotation planning), fill in the column titled “Field type,” also; otherwise, leave this

column blank. See the first three columns of table 5.6 for an example. (Hint: If you commonly plant several crops and cover crops on individual MUs within a single season, leave a blank line between units so you will have enough room to include them all when you fill in the crops later.)

18. Fill in our map data.

Copy the information you noted on the maps into the blank columns of the Field Conditions Worktable. This puts the map data in a form that allows you to sort management units on the basis of their characteristics. Using your maps of valuable fields and problem fields, label a blank

column for each different type of characteristic you noted (for example, “erosion potential,” “soil quality”; see table 5.6). Then record information about each MU in the appropriate box.

19. Record your recent cropping history.

Fill out the columns in the Field Conditions Worktable describing the cropping history for each management unit for the past three years. Write the actual year above “Crop 3 summers ago.” This planning procedure assumes that you are doing your planning in the winter and thus begins with the current winter’s cover or cash crops. Write in the names of current crops and their planting and expected harvest times. Now work backward from the present to preceding years as you go from right to left. If more than one cash or cover crop was grown during a given period, enter both names into the cell in the order they will be grown using a slash (/) as a separator (for example, spelt/hay). If two crops were grown on different parts of an MU in some past year, for the sake of simplicity, just enter the name of the crop that covered the largest portion of the MU.

Table 5.7 (page 78) shows the cropping history of Small Valley Farm.

20. Sort the management units.

Cut your completed Field Conditions Worktable into strips to separate the management units. Management units with similar histories often do not need to be separated. If you did steps 9 and 10, group the strips by field type. Arrange the strips so that, within each field type, (1) units with similar crop histories are together; and (2) within those groups, adjacent management units are in numerical order. If you skipped steps 9 and 10, arrange the strips so that (1) MUs with similar critical field conditions are together; (2) within those groups, MUs with similar crop histories are together; and (3) within each crop history group, adjacent management units are in numerical order.

Everyone: For this purpose “similar crop histories” means similar in how the history affects what crops you will grow in the future. For example, if one management unit had broccoli and another had cauliflower two summers ago but otherwise their histories do not differ, you may decide that they are not sufficiently different to warrant separating them into different groups for planning future crop sequences. Use coins or other weights to hold the strips in place while you sort them. When you are satisfied with your sorting, tape the strips to a piece of paper with clear tape, so that you have a permanent record of the cropping history of the farm in terms of your newly defined management units.

After the Small Valley farmers sorted their MUs, units 9 and 10 were grouped with the other flat, ordinary MUs (units 1–4). Similarly, the steep MUs (units 5–8, 11, and 12) were grouped together (table 5.8, page 80).

| Table 5.6 Example of the field characteristics portion of the Field Conditions worktable (table 5.2, pages 62–63) for Small Valley Farm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field name | Field type | Mgmt. unit | Erosion potential | Soil quality |

| C | I | 1 | low | good |

| C | I | 2 | low | good |

| A | I | 3 | low | good |

| A | I | 4 | low | good |

| A | II | 5 | high | fair |

| A | II | 6 | high | fair |

| A | II | 7 | high | fair |

| A | II | 8 | high | fair |

| B | I | 9 | low | good |

| B | I | 10 | low | good |

| B | II | 11 | high | fair |

| B | II | 12 | high | fair |

| D | III | 13 | very low | very good |

| D | III | 14 | very low | very good |

| D | III | 15 | very low | very good |

| D | III | 16 | very low | very good |

| D | III | 17 | very low | very good |

| D | III | 18 | very low | very good |

21. Number the management units on the Field Futures Worktable.

Number the MUs on the Field Futures Worktable (your copy of table 5.3, pages 64–65) in the sequence in which they appear on your sorted Field Conditions Worktable. Also fill in the field name and, if you did steps 9 and 10, the zone. For example, MU 9 appears on line 5 of both the sorted Field Conditions Worktable and the Field Futures Worktable for Small Valley (table 5.8, page 80).

| Table 5.7 Cropping history of Small Valley Farm (part of their Field Conditions worktable) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field name | Field type | Mgmt. unit | 3 years ago | 2 years ago | Last year |

| C | I | 1 | corn | soybean | oat/clover/spelt |

| C | I | 2 | corn | soybean | oat/clover/spelt |

| A | I | 3 | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay |

| A | I | 4 | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay |

| A | II | 5 | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay |

| A | II | 6 | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 |

| A | II | 7 | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 |

| A | II | 8 | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 |

| B | I | 9 | corn | soybean | oat/clover/spelt |

| B | I | 10 | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/oat cc |

| B | II | 11 | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/oat cc |

| B | II | 12 | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/oat cc |

| D | III | 13 | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn |

| D | III | 14 | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn |

| D | III | 15 | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn |

| D | III | 16 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean |

| D | III | 17 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean |

| D | III | 18 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean |

22. Plan the next growing season.

Look at your completed crop worktable (your version of table 5.1, page 61) and note how many management units of each crop you plan to grow. Fill in the names of the crops you will grow on each MU next summer. If more than one crop will be grown on an MU, write them all in

the cell in the sequence they will be grown (for example, “lettuce/buckwheat cc/fall broccoli”). Place crops in the following order, referring to your field conditions maps as needed:

Points to take into account when placing crops:

For those developing a general rotation plan (you did steps 9 and 10 above); others skip to step 23: Most of the considerations discussed above are essentially covered by your general rotation plan. The key for placing crops next season is to begin converting from the previous cropping history to the general rotation plan. This requires looking forward more than just one year. Getting each MU on track requires some imagination and a lot of trial and error (on paper). Remember, however, that once you have the desired crop mix within a field type, future crops can follow more or less automatically. If your general rotation plan is based on crop categories (for example, early-season greens, full-season nightshades) rather than specific crops, place the crop categories on the MUs first. Then go back through and place the specific crops within each category.

Consider the example of Small Valley Farm in table 5.8 (page 80). In field type I last year they planted three management units of oat/clover/spelt. Ultimately, they would like to get one MU of field type I into each of the six cropyears of the six-year rotation. The spelt, however, is already

planted, and they are loath to plow it under. This results in three MUs of spelt in field type I next spring and none in field type II, where they would ultimately like to have it.

In MUs 1, 3, and 10 they simply proceed into the planned next crop. Instead of overseeding hay into the spelt in MU 2, they overseed with clover next spring and then plant oat followed by spelt two years from now. Similarly, instead of overseeding hay into the spelt in MU 9 they overseed red clover, and then plant corn the following year. To get MU 4 on track, they treat the overseeded hay as a cover crop and plant oat followed by spelt next summer. Thus, by two years from now, they have one of each of the six crop-years on one MU of field type I, and the rotation plan is in place for that field type of the farm.

Similar slight departures from their desired sequences are necessary in the other two field types. Most notably, in field type II they grow oat as a hay crop on MU 11 next year and on MU 12 two years from now to make up for the shortage of grass-alfalfa hay. Except for the substitution of oat hay for their usual grass-alfalfa hay, note that they grow the desired crop mix in each future year. Note also that they meet their explicit goal of avoiding the same crop immediately in succession. Three years from their planning exercise, the rotation plan has been implemented for the whole farm.

23. Check next growing season's crop mix.

After you have assigned crops to all MUs, add the number of MUs of each crop. Compare these with the number of MUs you intended to grow, as indicated on your Crop Characteristics Worktable. If the two numbers do not agree, either assign some MUs to other crops or change

the planned number of units on the Crop Characteristics Worktable.

If you think it will be helpful, enter the planting and harvest times for next summer’s crops. The planting and harvest times are most useful when you plant the same crop multiple times during the season (for example, succession plantings of lettuce or spring and fall broccoli crops). See sidebar 5.3 (page 70) for a simple system of codes for recording planting and harvest times.

24. Plan next winter and two growing seasons from now.

Fill in any cash crops that will be present next winter (for example, garlic, spelt). Do not assign winter cover crops yet. Fill in cash and cover crops for two summers from now as you did for next summer (see step 22).When making decisions, always look back over the whole cropping history of the management unit up to this point, as well as the special properties of the MU. Refer to appendix 2 (pages 104–123) to check for potential problems and opportunities. Check your crop mix, as in step 23, to be sure that the field plan provides the correct amount of each crop.

Now fill in cover crops for next winter that make sense given the crops that precede and follow them. Consider especially (1) the harvest time of the preceding crop, (2) the planting time of the following crop, and (3) the needs of the following crop (N demand, ability to incorporate

cover crop before planting, etc.).

| Table 5.8 Recent crop history and future crop sequences for Small Valley Farm (continues on next page) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field name | Field type | MU | 3 years ago | 2 years ago | Last year | Next year | 2 years from now |

| A | I | 1 | corn | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 |

| A | I | 2 | corn | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/clover cc | oat/clover/spelt |

| B | I | 3 | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/oat cc |

| B | I | 4 | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay |

| C | I | 9 | corn | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/clover | corn |

| C | I | 10 | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean |

| B | II | 5 | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/spelt |

| B | II | 6 | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3 | hay4/spelt |

| B | II | 7 | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/spelt | spelt/hay |

| B | II | 8 | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/spelt | spelt/hay |

| C | II | 11 | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | oat hay/hay | hay2 |

| C | II | 12 | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | soybean | oat hay/hay |

| D | III | 13 | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean | oat/clover cc |

| D | III | 14 | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean | oat/clover cc |

| D | III | 15 | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn | oat/clover cc | corn |

| D | III | 16 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean | oat/clover cc | corn |

| D | III | 17 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean | corn/ryegrass | soybean |

| D | III | 18 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean | corn/ryegrass | soybean |

25. Plan future years.

Repeat, as in step 23, for each succeeding year. Plan as far ahead as you feel will be useful. Realize that your plans may need to change due to weather events and market conditions.

| 3 years from now | 4 years from now | 5 years from now | 6 years from now |

| corn | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | |

| hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn | |

| corn | soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay |

| hay2 | hay3/oat cc | corn | soybean |

| soybean | oat/clover/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 |

| spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/oat cc | |

| spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/spelt | spelt/hay |

| spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3/spelt | spelt/hay |

| hay2 | hay3/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 |

| hay2 | hay3/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 |

| hay3/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3 |

| hay2/spelt | spelt/hay | hay2 | hay3 |

| corn | soybean | oat/clover cc | corn |

| corn | soybean | oat/clover cc | corn |

| soybean | oat/clover cc | corn | soybean |

| soybean | oat/clover cc | corn | soybean |

| oat/clover cc | corn | soybean | corn |

| oat/clover cc | corn | soybean | corn |

26. Put your plans on maps.

Copy the information from the Field Futures Worktable onto blank maps. Put the crops for next summer on one map, the crops for next winter on another, etc., for as many seasons as you have planned ahead.

27. Take the maps to the field

Take these maps and walk through your fields. For each cluster of adjacent MUs, farm the cropping sequence through in your head. Compare the maps with your feel for the various management units and how they have performed in the past. Take notes on what seems right and what may not work.

Write down what you could do if problems arise. This is an important consideration. Think about what will happen if rain delays timely incorporation of a cover crop or timely planting of a cash

crop. What will you do if cultivation is delayed and the crop becomes excessively weedy? Consider other potential problems and whether they may require a change in the planned sequence. Make notes on potential alternative strategies to meet circumstances you may encounter.

28. Modify planned sequences.

Return to your office (or kitchen table) and lay out your maps and notes. Based on insights gained from walking the fields, modify the planned sequences where necessary on the Field Futures Worktable.

29. Recheck your crop mix.

When you have a reasonable plan, add up the numberof MUs of each crop in each year and check this against your intended production, as indicated on the Crop Characteristics Worktable.

Make further adjustments on the Crop Characteristics Worktable or the Field Futures Worktable if necessary. Remember, however, that year-to-year variation in productivity may swamp out slight variation in the number of MUs grown for major crops.

| Table 5.9 Crop characteristics worktable for Summer Acres Vegetable Farm | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop | Acres/year | MUs/year | Family | Plant Time | Harvest Ends | Harvested Part | Cold Tolerance |

| 0.16 | 2 | Lily | lfall | msum | root | very hardy | |

| Pea | 0.32 | 4 | Legume | espr | msum | fruit | hardy |

| Lettuce 5 | 0.16 | 2 | Lettuce | espr | esum | leaf | half-hardy |

| Lettuce 6 | 0.16 | 2 | Lettuce | esum | msum | leaf | half-hardy |

| Lettuce 7e | 0.16 | 2 | Lettuce | msum | lsum | leaf | half-hardy |

| Lettuce 7l | 0.16 | 2 | Lettuce | msum | efall | leaf | half-hardy |

| Lettuce 8 | 0.16 | 2 | Lettuce | lsum | lfall | leaf | half-hardy |

| Potato | 0.32 | 4 | Nightshade | lspr | lsum | root | half-hardy |

| Tomato | 0.48 | 6 | Nightshade | lspr | efall | fruit | tender |

| Pepper | 0.24 | 3 | Nightshade | lspr | efall | fruit | tender |

| Carrot | 0.16 | 2 | Carrot | espr | efall | root | half-hardy |

| Kohlrabi | 0.08 | 1 | Mustard | espr | msum | leaf | hardy |

| Broccoli | 0.16 | 2 | Mustard | lspr | lsum | flower bud | hardy |

| Summer squash | 0.24 | 3 | Cucurbit | esum | efall | fruit | tender |

| Winter squash | 0.48 | 6 | Cucurbit | lspr | efall | fruit | tender |

| Spinach 5 | 0.16 | 2 | Beet | espr | esum | leaf | hardy |

| Spinach 8e | 0.16 | 2 | Beet | lsum | efall | leaf | hardy |

| Spinach 8l | 0.16 | 2 | Beet | lsum | lfall | leaf | hardy |

| Beet 5 | 0.08 | 1 | Beet | lspr | msum | root | half-hardy |

| Beet 7 | 0.08 | 1 | Beet | msum | Ifall | root | half-hardy |

| Total | 4.08 | 51 | |||||

| 1 The number after the names of some crops refers to the planting month; e and l refer to early and late in the month. 2 Abbreviations for planting time and the end of harvest are given in Sidebar 5.3 (page 70). | |||||||

30. Note your contingency plans.

When you have the Field Futures Worktable adjusted

the way you want it, add notes indicating your contingency plans (see your field notes from step 27). Enter these either in the margins if they are few or on a separate piece of paper if there are many. If necessary create a separate page to show the contingency plans for a given group of MUs. Staple the contingency plans to the Field Futures Worktable, so that they stay together.

Small Valley has multiple possibilities for meeting contingencies. For example, if weather hopelessly delays planting of oat, the farmer can substitute corn. Similarly, soybean can be substituted if planting corn is not feasible. If plowing down the hay or planting spelt proves impos- sible, the hay can be left for an extra year. Each of these essentially moves the rotation ahead one year, which is fairly easy to compensate for in the future. Obviously, all of these circumstances result in a crop mix that is differ- ent from the original plan, but that is necessarily the case when a crop cannot be planted.

The Small Valley example also illustrates potential for adjusting the crop mix to meet market demand without significant modification of the basic rotation plan. For example, a different spring grain could be substituted for oat, dry bean or snap bean for soybean, or a heavy-feeding vegetable crop like cabbage or pumpkin for corn.

31. Make your crop placement maps match your revised Field Futures Worktable.

Finally, modify the maps for each year so that they match the Field Futures Worktable. Make several copies of these maps so that you can take them into the field when you are preparing seedbeds and planting while still retaining a clean copy for your records.

Congratulations! You have created a complete cropping plan for your farm. Be prepared to modify it as you gain knowledge and experience. Continue to grow with your farm.

This site is maintained by SARE Outreach for the SARE program and is based upon work supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award No. 2021-38640-34723 . SARE Outreach operates under cooperative agreements with the University of Maryland to develop and disseminate information about sustainable agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in SARE publications are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture or SARE. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.